Record Details

Phrenological Head

When Asa Ames carved this strange and beautiful portrait of a young girl with incised and colorful markings on her scalp, he was testifying to a runaway offshoot of Enlightenment faculty psychology that presented itself as a scientific method for self-improvement. Phrenology was conceived in medical circles as a serious study of brain structure as it related to the human mind. The brain was divided into twenty-seven faculties; it was later proposed that the formation of the skull itself conformed to these faculties.

In America, brothers Lorenzo and Orson Squire Fowler promulgated a form of practical phrenology: through an examination of the bumps on a person’s head, one’s nature could be analyzed and recalibrated with a program of exercise or by neglect of specific faculties. The Fowlers were major advocates of social reform and published on subjects promoting the benefits of health food, homeopathy, hydropathy, and mesmerism, and also agitating for women’s and children’s rights, sex education, and other reforms and therapies. The era of self-improvement was now the age of self-help.

Shortly before his death, Asa Ames was living in the household of Dr. Harvey B. Marvin, a homeopath, physician, and practitioner of alternative therapies. It is likely that the Phrenological Head was carved around the time of this association. There is no real precedent for the three-dimensional portraits in wood by Ames that are known today. The flat base of the waist- and bust-length carvings seems to derive from a beautiful but short-lived stone-carving tradition in Renaissance Florence, perhaps innovated by Desiderio da Settignano. Like much painted portraiture of the day, the representations are direct, frontal, and iconic in their minimalist simplicity.

Stacy C. Hollander, “Phrenological Head,” exhibition label for Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum. Stacy C. Hollander and Valérie Rousseau, curators. New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2014.

Phrenology was conceived in Vienna near the turn of the nineteenth century by Dr. Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828), whose studies into the organic structure of the brain resulted in his theory that the brain could be divided into thirty-seven "faculties" that are responsible for aspects of behavior. One of his students, Dr. Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832), expanded Gall's theories, further positing that the formation of the cranium conformed to the faculties, and that by examining the skull an understanding could be gained of a person's natural propensities. Before midcentury, phrenology had passed from medical circles to a wide popular base in America, primarily through the efforts of two brothers, Lorenzo and Orson Squire Fowler, and the army of itinerant phrenologists they spawned. As a result, phrenology lost much of its scientific credibility but played perfectly into the sense of restlessness that characterized the Age of Reform, especially through the Fowlers' publications, which promoted radical therapies and reforms such as the abolition of slavery, women's and children's rights, sex education, health food, and temperance.

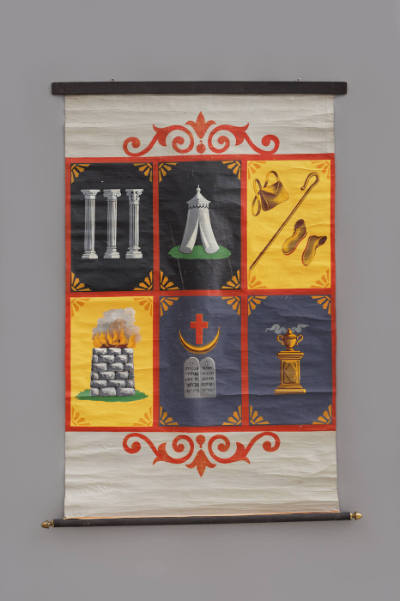

Phrenological heads cast in plaster or ceramic became commonplace adornments in American homes; according to an article in the Boston Christian Examiner in 1834, "Heads of chalk, inscribed with mystic numbers, disfigured every mantelpiece." This unusual phrenological head is attributed to Asa Ames, who is known for a small group of portrait busts and full-length carvings, mostly of children, created between 1847 and 1851, the year of his death. The carvings are characterized by a sense of quiet in the beautifully modeled faces, the treatment of hair as a series of precise incised lines, and the careful details of dress. The museum's phrenological head was probably carved in 1850, while Ames was living with the family of Dr. Harvey Marvin in upstate New York. Dr. Marvin had dabbled in phrenology and other alternative medicines and was in the process of establishing a hydropathy, or water-cure, clinic at the time; Ames was suffering from tuberculosis, and town tradition states that he was under Dr. Marvin's care. The bust sheds light on the proliferation of phrenology into even the most rural areas by the middle of the nineteenth century and stands as a poignant testimony to the artist's search for a cure before the age of antibiotics.

Stacy C. Hollander, "Phrenological Head," in American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (Harry N. Abrams in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2001), 337.