Record Details

Masonic Plaque in the Form of a Royal Arch Tracing Board

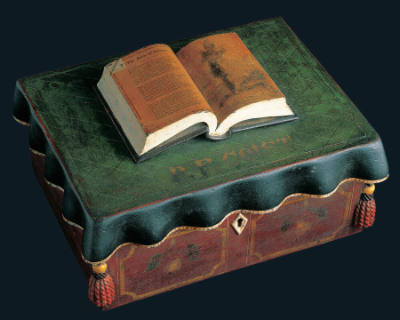

The origins of Freemasonry remain obscure. The secret society traces its roots to Solomon’s Temple, but more likely it arose out of the practices of medieval stonemasons’ guilds. Modern Freemasonry dates back to seventeenth-century England and was well established in North America by the time of the American Revolution. Indeed, during the new republic’s first fifty years, Masonic symbolism seemed to permeate American culture almost as Christian imagery permeated the art of the Middle Ages.

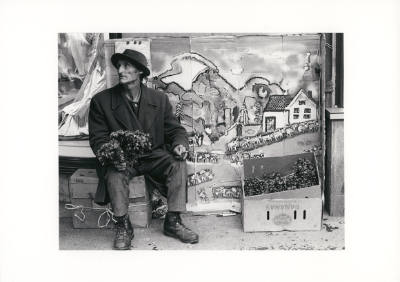

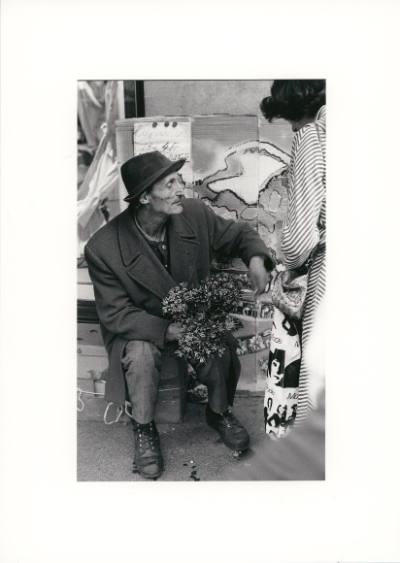

Following a period of decline during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, American Freemasonry began to regain its popularity after the Civil War. Freemasons and the members of their families incorporated Masonic motifs into a wide variety of decorative and household objects—woodcarvings, pottery, furniture, quilts. These are characterized by a more Victorian and personal interpretation than earlier Masonic objects, which tended to be formal and adhere strictly to neoclassical tradition.

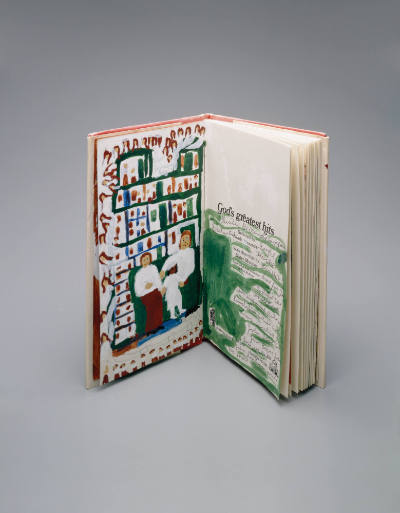

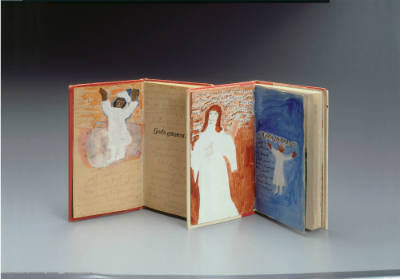

The role of memory and mnemonic devices is central to an understanding of Freemasonry. Since Masonic teaching is intended for initiates, Masons use emblematic devices and coded language to convey esoteric messages and commit them to memory. Master’s charts—also called “carpets” or “tracing boards,” whether painted or printed—illustrate Masonic precepts through complex symbolic displays. Although this plaque is related in content to the tracing boards of Royal Arch Masonry, one of several symbolic systems within Freemasonry, it seems unlikely that it was used in formal ceremonies. Rather, it appears to have been intended for display in the home of a Freemason as a sign of prestige and pride.

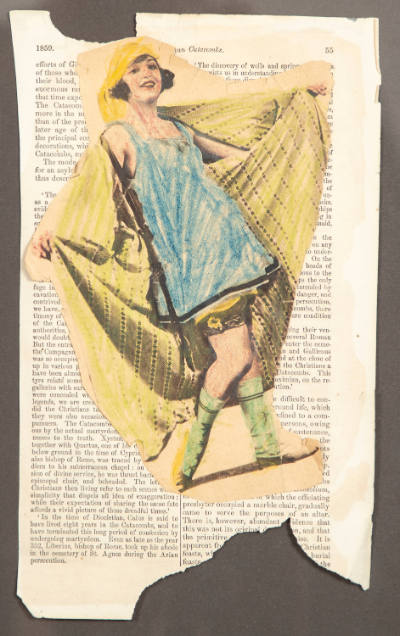

The biblical accounts of the building of Solomon’s Temple inspire much Masonic ritual and imagery. The arch that dominates this handsome plaque is a reference to the Temple and is an emblem of Royal Arch Masonry. In the upper right, the artist has included a Tau Cross, or Cross of St. Anthony, which is composed of three Ts and is a symbol of Deity. When enclosed in a triangle and circle, as here, it is recognized as the badge of Royal Arch Masonry. The series of letters that surround the compass in the arch’s keystone is a mnemonic device associated with Royal Arch Masonry’s Mark Master degree. The ascending letters on the ladder stand for “faith,” “hope,” and “charity.”

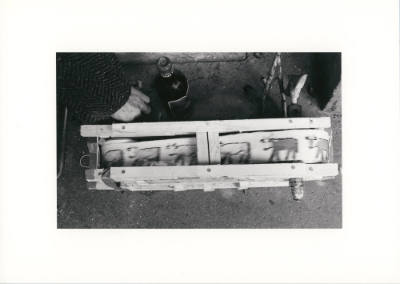

This plaque is a tour de force of technique and design. The unidentified artist used a variety of applied wood chips, veneers, and carved elements, combined with printed and painted paper, to create a remarkably well-balanced composition that dazzles the eye. Decorative devices share the plaque’s space harmoniously with Masonic imagery. The influence of quilt motifs, especially late-nineteenth-century Crazy or show quilts, and perhaps of game boards, is apparent. The center door seems to be at the end of a receding hallway, which in reality is an entirely flat surface. The door opens to reveal a small drawing of two men.

The object contains a hint of its maker’s identity. The year “1899” is inscribed on the back of the plaque, and is accompanied by an advertisement for J.M. Forbush & Co., an insurance agency that operated in Natick, Massachusetts, from about 1882 to 1905. Interestingly, there was a local Mason named James M. Forbush who entered Natick’s Meridian Lodge in 1871 but withdrew in 1894.

Gerard C. Wertkin, "Masonic Plaque in the form of a Royal Arch Tracing Board," in Stacy C. Hollander, American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2001), 357.

Object information is a work in progress and may be updated with new research. Records are reviewed and revised, and the American Folk Art Museum welcomes additional information.

To help improve this record, please email photoservices@folkartmuseum.org