Record Details

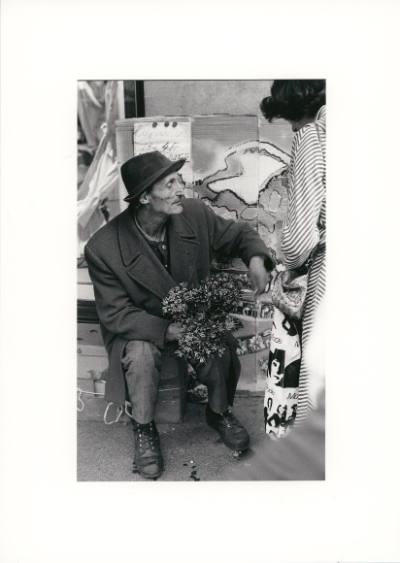

Hans Krüsi, Zürich, 1978

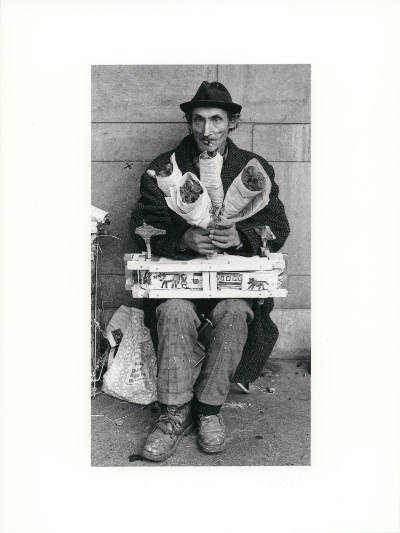

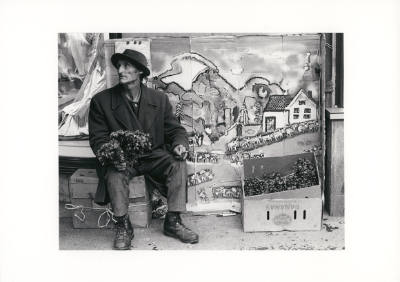

I have strong memories of visiting Zurich in my childhood and seeing a man on Bahnhofstrasse, a luxurious street lined with banks and shops. The man was Hans Krüsi (1920, Zurich, Switzerland–1995, St. Gallen, Switzerland). At that time, he traveled to Zurich regularly from St. Gallen, to sell flowers and his artworks from a stall. Krüsi’s first gallery exhibition was in 1981, and in the eighties Krüsi gained more visibility.

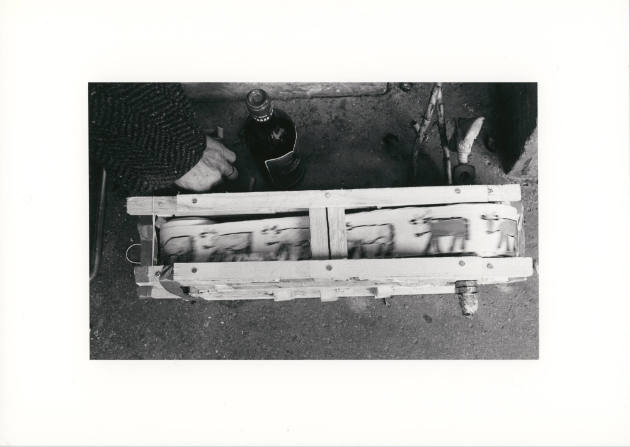

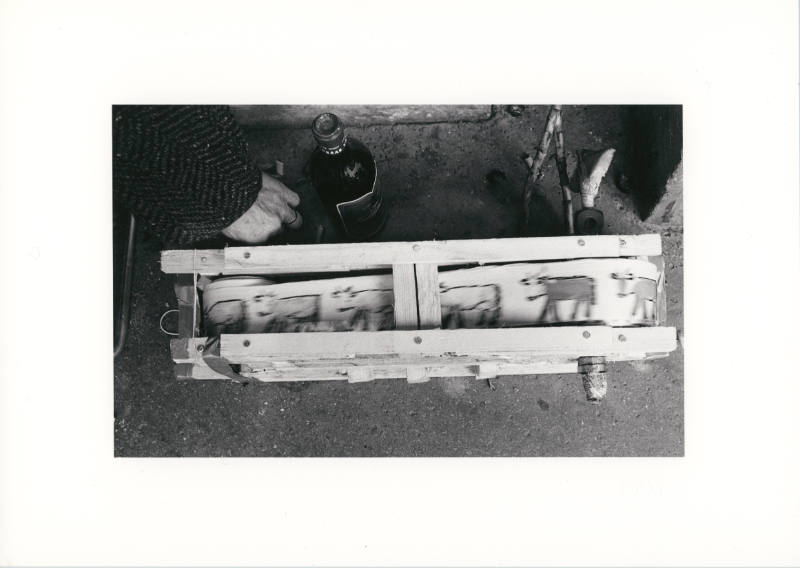

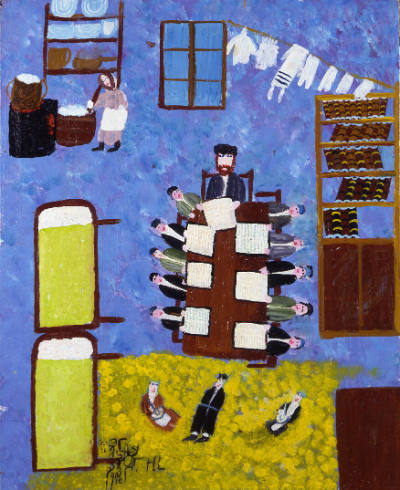

Krüsi was all about an encyclopedic don’t-stop principle. His whole studio was filled with tens and tens of thousands of drawings and sketches and stencils with many motifs, but mainly of cows, which he then transformed into “cow machines.” Krüsi grew up on a farm owned by his foster parents, spent much of his time alone, and as an adult he moved frequently and survived at the margins. He started selling flowers on Bahnhofstrasse in the mid-1970s, and soon started to sell postcard-size paintings. Most of them are pastoral scenes. I don’t really know the word for Alpaufzug in English. It expresses a ceremony, almost a “return”: it’s the transfer of cattle up the hills to the Alps for summer pasture. And he painted many of these Alpaufzugs: it was an obsessive thing of repetition and difference.

Whenever he was in a café or restaurant, Krüsi would draw or stencil on napkins. He always had dozens and dozens of stencils with him. In letters he sent to me, at first he only included his address, and later he started to include Kunstmaler (artist-painter). Little by little, he replaced his address with a cow.

If we really look at poetry and literature and architecture, they have in one way or another been influenced by cinema. Krüsi always said that. His drawing activity led to these cow machines, which are almost cinematographic, filmic depictions of Alpaufzug. The Alpaufzug is about movement—so Krüsi decided at a certain moment to animate his drawings.

There was also a Warholian dimension to Krüsi, because he obsessively recorded everything. His studio was full of old cameras and obsolete recording devices. He would record birds and the sounds of cows. Krüsi also liked bells, because they were a way of mapping the city—so he recorded all the bells in St. Gallen. Going to his studio was like experiencing a work of art without any divisions: paintings, then sound, then architecture. In Krüsi’s studio it all came together at once—all the senses, all the arts.

Adapted from Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Hans Krüsi” in Valérie Rousseau (ed.), When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2015).

Object information is a work in progress and may be updated with new research. Records are reviewed and revised, and the American Folk Art Museum welcomes additional information.

To help improve this record, please email photoservices@folkartmuseum.org