Born into a family of shopkeepers in the Tunisian Jewish community, Jean-Daniel Allanche left in 1958 for France, where he became a citizen and defended two doctoral dissertations on physics in succession. A noted researcher, he published articles in theoretical physics, his area of expertise. From 1970 to 2001, he was a professor in physics at the University of Paris VII, except for a ten-year period, during which he was hired by the French government to teach quantum mechanics and electromagnetism in newly founded universities in Africa.

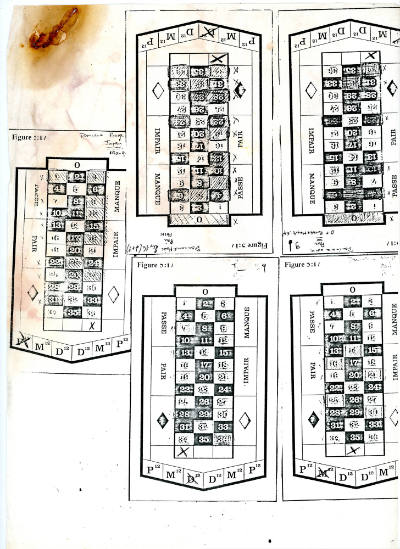

At the same time, living in self-imposed solitude, Allanche devoted himself to learning music and languages, wrote poetry, and painted in diverse styles. He also wrote articles on correlation and chaos methods applied to games. This theoretical research, aimed at establishing winning combinations for roulette and bowls, is illustrated in a dozen notebooks, each of which contains hundreds of pages. They are embellished with equations, number sequences, and symbols, written with blue, red, green, and black ballpoint pen, erased in places with white correction fluid, and accompanied by annotations that give information on the behavior of the players and croupiers, whom he believed had an impact on the results. Some signs are carefully displayed with color coding. Allanche’s sustained attention to gambling nevertheless found existential ramifications. In 1976, he wrote, “Life is a game that is exciting only if the stakes are high. It is our work (action) that makes the stakes important. They are our wishes for success in the form of elevations of matter or the possibilities of human beings. Solution: trying to become a musician, a scholar, a writer . . . is hard but necessary.”

Allanche’s works have the texture of skin tested by the passage of time. Their surfaces reserve marks of wear created by friction, scratching out, and retries; impregnated with his body oils, they are yellowed by the repeated rubbing of his hands in their lower right corners, just as the accidents of daily life are grafted onto them. This recording of what is lived is reminiscent of Melvin Way’s approach: Way made small drawings that he folded, opened, and folded again to modify. Then, he put them in his pocket, against his body, sometimes for several months, as if they were protective amulets. Both Allanche and Way saw their work as being formed of a superimposition of sediments. The story thus formulated is blurred not only by the hermeticism of the signs, codes, and formulae that it contains, but also by the accumulation—even condensation—of version that held, for a time, their moment of truth. The final version of the cacophonic and enigmatic narrative built by piling up serves as the ultimate proposal, a figure of authority over the preceding ones. The laborious rendering of Allanche’s drawings thus resonates with this sentence engraved on his gravestone: “My painting is like dust that keeps the memory of life.”

Valérie Rousseau, “Jean-Daniel Allanche: Piling Up the Dust of Memories,” in Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic, ed. Valérie Rousseau (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2018).