Record Details

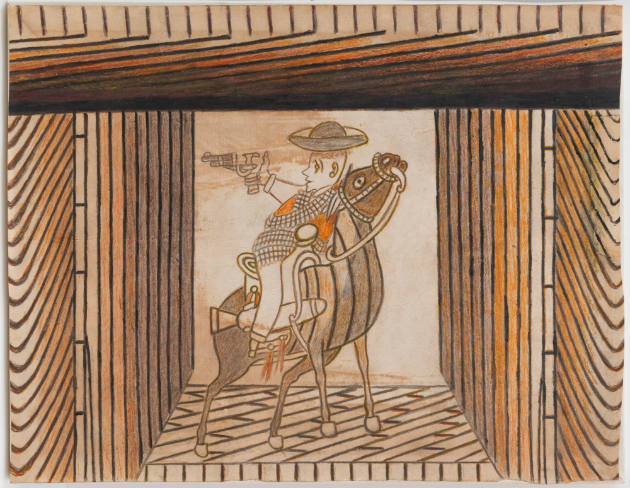

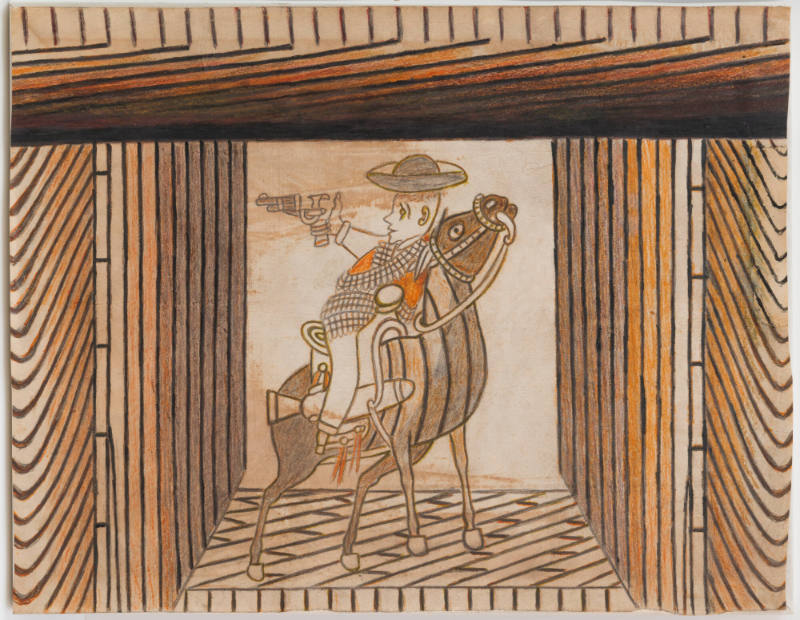

Untitled (Horse and Rider)

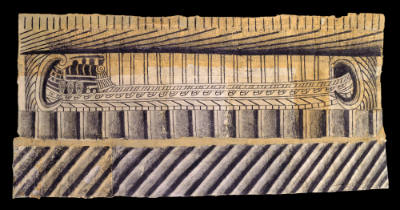

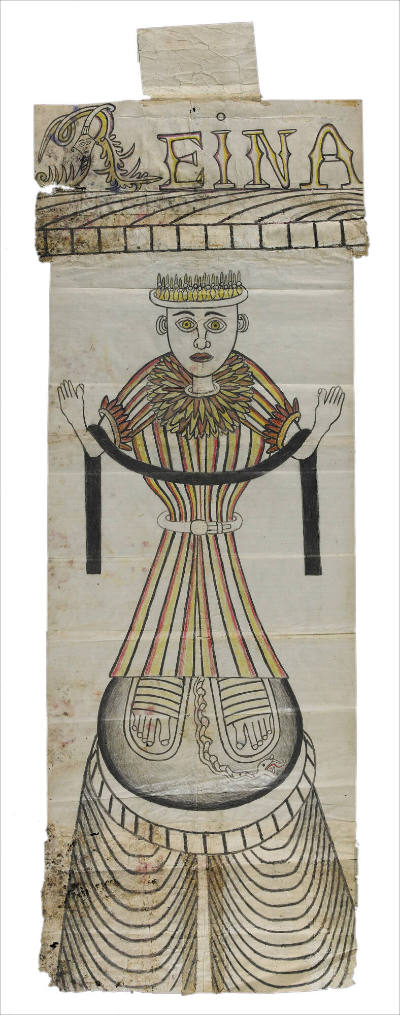

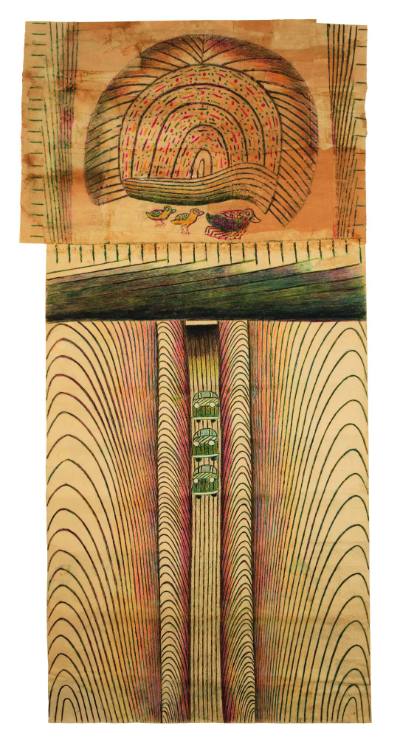

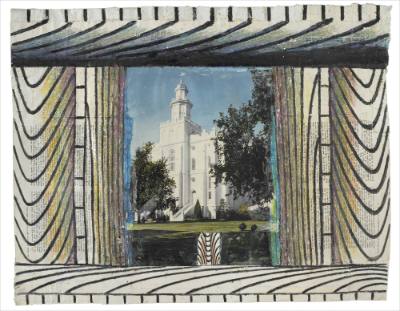

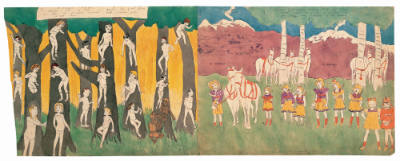

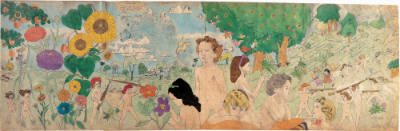

A struggling rancher from Jalisco, Martín Ramírez moved to the United States in 1925 to find better work opportunities, leaving his wife and children behind. He found railroad jobs, but the Great Depression left him unemployed. Ramírez was arrested in Sacramento in 1931, and spent the last thirty-two years of his life in various mental hospitals—notably, fifteen years (1948–1963) at the Dewitt State Hospital. He drew from the mid-1930s, but his 450 surviving drawings were mainly created from 1950 to 1956. Ramírez artworks range in size from two feet to twenty feet long. Instead of systematically using the paper available, he searched for discarded scraps of paper (e.g., correspondence, memos, envelops, and newspaper) in garbage cans at night. Then, he glued these finds together with a homemade adhesive that he fashioned out of saliva and oatmeal, bread, or mashed potatoes. If Ramírez painted with conventional materials such as crayons, watercolor, and ink, he also crafted mixtures with crushed crayons and colored pencils, pink matchstick heads, charcoal (from used matchsticks), and shoe polish, diluted with fruit juices, saliva, and sometimes phlegm. James H. Durfee, a psychiatric technician at Dewitt, said that Ramírez used tips of wooden matchsticks to apply his concoctions, as well as tongue depressors to trace lines instead of the rulers that he received. In his later works, he often collaged clipped images selected from visually rich American magazines, such as the Saturday Evening Post. In short, his fastidious technique shows that the process was important for him.

The oeuvre of Martín Ramírez features repetitive motifs: first and foremost, his signature wave-like lines or stripes, hypnotic and vibrant, with its illusion of movement, depth, and space; lots of horses and riders (of which he made about eighty versions); and trains emerging from tunnels, boats, trucks, and cars—all means of transportation that somehow counterweight the immobility of his hospitalization. Another celebrated theme is the queen of heaven and earth, the Virgin Mary, who takes various forms. Art historian Víctor M. Espinosa proposes that it might be an image of the artist’s wife, for whom he may have felt guilty for abandoning. He notes that “there is something human, something not sacred in the image.” Alluding to these subjects of which the artist made many versions, Espinosa suggests that his confinement might have been conducive to time-lag. These images from his homeland are frozen in his “conflicted memories.”

Valérie Rousseau, exhibition label for Memory Palaces: Inside the Collection of Audrey B. Heckler. New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2020.