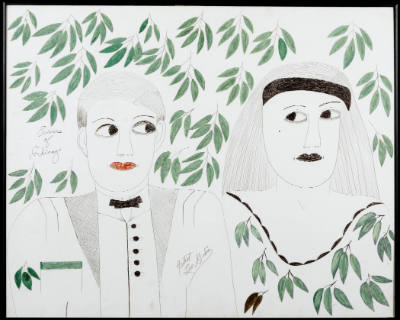

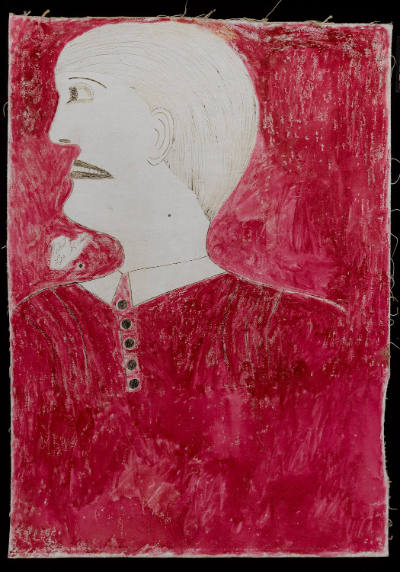

During the thirty years or so that she was a fixture of downtown Chicago, Lee Godie created two main bodies of work, both expressive of the glamorous identity she cultivated as the city’s own “French impressionist.” There were the drawings she sold in front of the Art Institute of Chicago—although with a prickly preference for who was worthy of owning them. These were made with a wide range of materials, such as watercolor, tempera, and pen, on surfaces including canvas, salvaged window shades, and pillowcases. These pieces, evoking a nostalgic world of refinement, featured animals, flora, and portraits, usually of women of idealized beauty, sometimes specific celebrities such as Clara Bow and Joan Crawford. Then there were the hundreds of self-portraits she started making in the 1970s in a bus station photo booth. She would dress in various outfits—sometimes styling herself as a femme fatale or a flashy socialite—paint colorful circles on her cheeks, and then add dramatic embellishments to the black-and-white prints with colored pencil and paint.

Godie was born in Chicago in 1908 and spent the majority of her life in the city. Although she regularly interacted with people, even debuting new work at themed parties, she was spare with details about her personal life. What is known is that she began reimagining herself as an artist sometime after the death of two of her children, and by 1968 she was living on the streets, often outdoors even in the freezing winters. Yet she promoted herself first and foremost as an artist, her studio being the city itself. “Chicago! A Heaven on Earth,” she frequently declared on her work.

Late in her life, she reconnected with her daughter and moved into a nursing home near Plano, Illinois. She died in 1994, just after the Chicago Cultural Center presented a retrospective of her work. She is often cited as the city’s most-collected artist, as the memory of her in her pieced-together fur coat on the steps of the Art Institute, boasting “Would you like to buy some canvases? I’m much better than Cezanne,” lives on in countless private and institutional collections.

Allison C. Meier, 2025

Text written as part of “Rethinking Biography,” an initiative supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).