Adolf Wölfli

(1864–1930)

BornBern, Switzerland

DiedBern, Switzerland

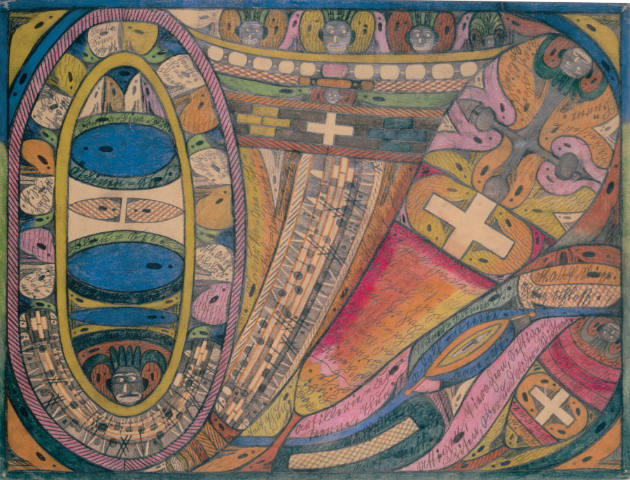

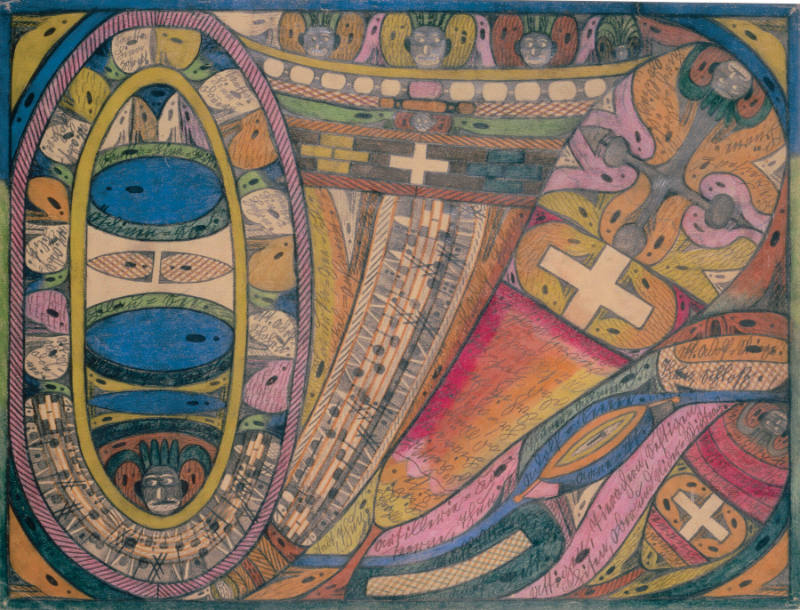

BiographyAdolf Wölfli was the author of a prolific and multifaceted artistic oeuvre that he began creating in November 1899, shortly after his hospitalization at the Waldau Mental Asylum in Bern. Between 1908 and 1930, he devoted himself to his magnum opus, St. Adolf-Giant-Creation, an illustrated narrative of 25,000 pages, comprising forty-seven volumes and sixteen notebooks. This imaginary autobiography, accompanied by 1,620 drawings and 1,640 collages made from pieced-together magazine fragments, is divided into five sections: “From the Cradle to the Grave,” “Geographic and Algebraic Books,” “Books with Songs and Dances,” “Album Books with Dances and Marches,” and “Funeral March.” Concurrently, Wölfli created about one thousand single-sheet drawings (1912–1930), which his doctor Walter Morgenthaler defined as “Bread Art.” Wölfli would trade these works with others in exchange for paper, colored pencils, and tobacco.His pictorial compositions suggest an ideal reading from above. Flattened out like maps that he would often call “plans,” they depict endless parades. These intricate landscapes are overcrowded with conscientious curving script, musical staves, avenues, buildings, and the figure of St. Adolf II, Wölfli’s alter ego. He explained that his hand merely translated the testimony of the tireless travels dictated by his memories, claiming that he really found and visited these places. Morgenthaler wrote that “Wölfli was of the kinesthetic type: he thinks with his pencil. It is often the gesture that provokes his thinking.”

Wölfli, who designated himself an “ear = musical = direct,” also composed and played music, which is a major component of his monumental narrative. Morgenthaler testified that he “makes music by blowing into horns made of thick paper bags, performing his tunes, marches, waltzes, polkas, and mazurkas. Rhythm is essential. As soon as he has developed a melody, he writes it.” In a rare archival document, Wölfli is photographed holding a roll of paper, and in another he is posed alongside two of these rudimentary instruments. His songwriting style is divided into two categories: compositions using notes and staves, and compositions displaying an alphabetical system of his own—what he called his “Algebra”—based on solmization (the attribution of syllables to notes). Since the 1970s, many composers have attempted to adapt Wölfli’s system. Some segments have been decoded, demonstrating that they were not purely decorative notations.

Adapted from Valérie Rousseau, “Adolf Wölfli” in Valérie Rousseau (ed.), When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2015).