William A. Hall

(1943–2019)

BornLos Angeles, California, United States

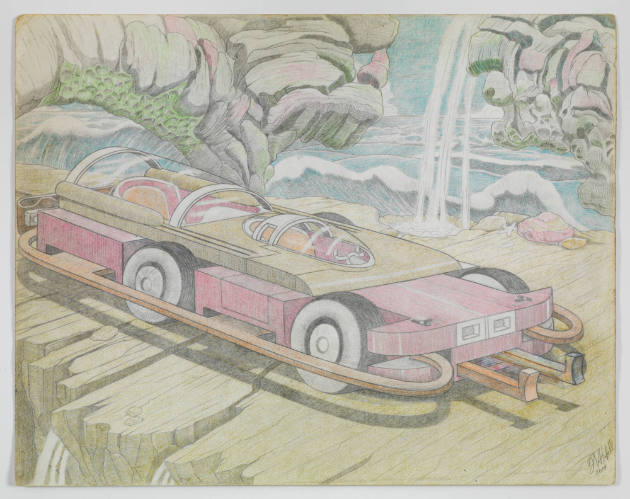

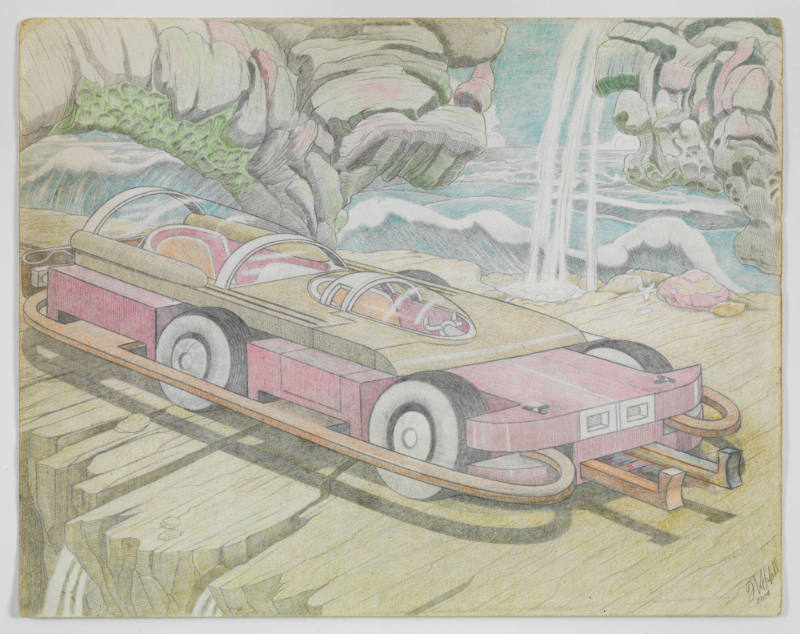

BiographyWilliam A. Hall’s drawings, with their intersections between fantasy and science fiction, have an intricate realism, with retrofuturistic cars cruising through rocky landscapes accented by gnarled trees, waterfalls, and shorelines with crashing waves. His compositions, made with colored pencil and graphite, expanded over days or even months and years as he worked meticulously on a panel at a time. This was a way for Hall to work on a large scale, as he made almost all his drawings while sketching against the steering wheel of his car—his home and studio for the final two decades of his life. His thirteen-page Pumpkin Castle Interior, with its Escher-like multitude of staircases overlooking tranquil blue water, has dates on the back of the panels timestamping its creation between October 2013 and January 2014. These notes are joined by his observations of daily life as he moved through various parts of Los Angeles, such as a monarch butterfly on the windshield or a flock of parrots flying overhead. Hall was born in 1943 in Los Angeles into a family of creatives; his grandfather was commercial illustrator T. Victor Hall. Hall himself, however, was self-taught aside from his elementary-school art classes. The death of his niece in a car accident in 1984 led to his obsession with safety and sanctuary, from the designs of his cars with their curved protective contraptions, to his drawings of peaceful dwellings such as Tree Motel, to the themes of his writing. His unpublished novel Protége, a manuscript accompanied by drawings he started in 2011, chronicles the Frankenstein-inspired journey of a giant called Xenos given life from cadaver parts to “protect us from the cruel predatorial humanoids.” Before he turned to drawing, he was focused on sculpture; then his mother died in 1997, and he had to move out of her house. “When I got put out on the street, I couldn’t make sculpture anymore,” he said in a 2016 interview with Hyperallergic. “In the streets, you have a whole different mindset.”

He gained recognition after he fortuitously parked on a block where some passersby noticed his work and connected him to artist Stephen Holman and gallery owner Henry Boxer. A 2016 publication on his art and its presentation in 2017 at the Outsider Art Fair in New York followed. In 2018, his illustrated narratives were featured in Vestiges and Verse at the American Folk Art Museum. He died in 2019.

Allison C. Meier, 2025

Text written as part of “Rethinking Biography,” an initiative supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).