Richard Saholt

(1924–2014)

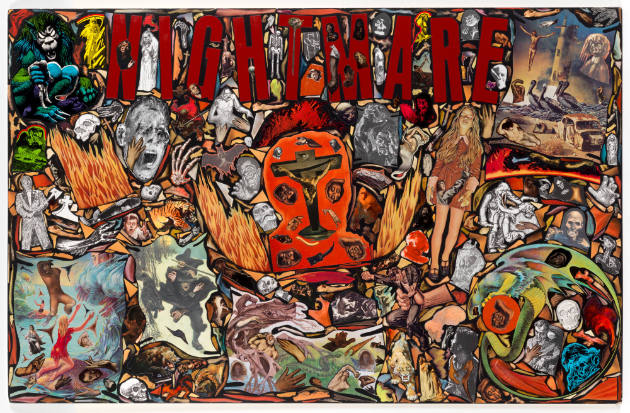

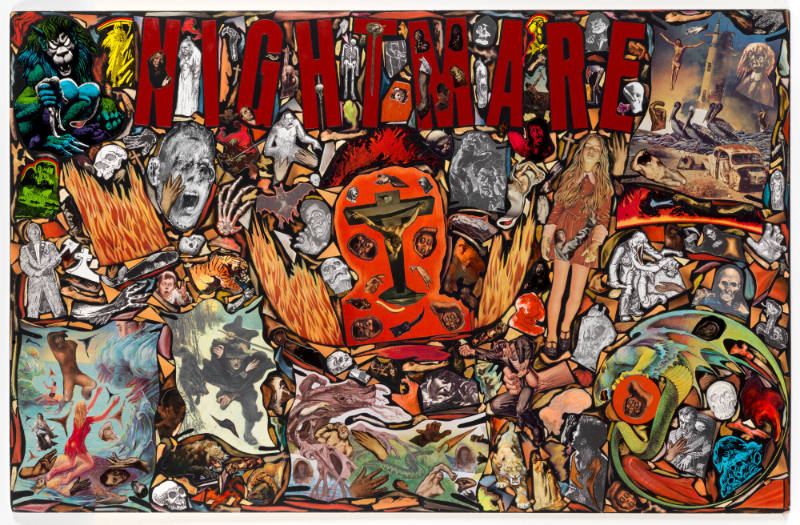

The anger that Saholt felt from the army’s deception, compounded with its refusal to award his disability benefits, found their way into the small collages that marked the beginning of his art-making practice in the mid-1960s. Among his collage works dating from the late twentieth century are several appropriated and repurposed books. One of them is an elaborately enhanced photograph album, The Chemistry of Madness—a title that refers to Saholt’s attempt to understand the physiological causes of his mental and physical illnesses. He used the blank pages of the photo album to attach newspaper and magazine articles on the subjects of schizophrenia and hypoglycemia, as well as his own handwritten notes, plus collaged images and words. The cover of the album wastes no time informing the viewer about how incompetent, veteran hospital doctors denied that he had hypoglycemia. The plethora of articles packed into the collages within the album may have been a way for him to explain and validate his condition to an intended audience that he hoped would read them. On the inside surface of the front cover, Saholt attached an article on schizophrenia, including a list of “schizophrenia’s danger signs,” to which he has added reproductions of Louis Wain’s famous portraits of cats that presumably marked the stages of Wain’s mental illness. Words from other sources are collaged over the cat pictures and article’s text: “sordid life,” “hell,” “madman,” “worrying,” “monsters,” “crazies,” “deadly,” “damned,” and “tragedy.” Areas of the printed article are circled and underlined in red and black ink. In every area of white space, Saholt adds his own handwritten sentences.

The album continues for some forty more pages with texts and images collaged together chock-a-block in obsessive compositions. Fine print and bold headline texts dominate the pages, sometimes collaged sideways so that the viewer must turn the book in various directions to read it. Occasionally, a page will contain predominantly images, but this is rare. Saholt seemed bent upon using the printed word as his primary vehicle of expression. As his collages grew to their most regular, frequent, and standard size, he continued to incorporate numerous blocks of newspaper or magazine text along with bolder words and images. However, as he became more confident using images and individual words alone to convey his messages, he apparently relied less often upon articles from publications as major components in his collages.

Michael Bonesteel, “Richard Saholt: The Chemistry of Madness,” in Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic, ed. Valérie Rousseau (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2018).