Seen from above, the compound is rambling and haphazard, isolated from all signs of life. It is situated on Calico Ghost Town Road, in Yermo, California, a lonely, featureless expanse of the Mojave Desert. It is here that Cal and Ruby Black made a life together on land that they purchased sight unseen from a magazine ad and called “possum trot,” an old southern expression for a shortcut between two locations. Who knows what they thought once they arrived at their new home in the middle of nowhere. They had no children, but they had each other and their faith, their hardworking ethic, and Cal’s talents and can-do optimism. Over time, they filled the emptiness with the sound, animation, and phantasmagoria of more than eighty child-size female figures, ramshackle structures, moving trains, merry-go rounds, stage coaches, and covered wagons, Ferris wheels, totems, signs, and paintings.

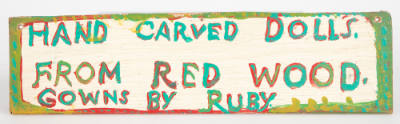

The Blacks were rural southerners. Cal was born in Tennessee, and Ruby was from Georgia, where they met while he was traveling with a circus and carnival. They were married in 1933, and moved to California, where Cal panned for gold. But standing in frigid waters for hours at a time, year after year, took its toll, and in 1953, they relocated to the desert, hoping the change would improve his health. The year that Highway 15 was extended along their stretch of land, the Blacks started a rock and tourist shop, hoping to attract passing motorists. Business was slow, and Cal conceived the idea of carving lifelike dolls that he would station around the property, alone and in vignettes, positioned high and low. Using a hatchet and pocketknife, he shaped figures from downed redwood telephone poles, with sugar pine for noses, and arms and legs that would swing eerily in the dry desert wind. Ruby refashioned outfits from cast-off clothing that grew more and more tattered through exposure with each passing season. The compound became ever more populated and the dolls more elaborate as the Blacks collaborated on shaping each personality, naming and discussing character, deciding eye and hair coloring, and choosing appropriate clothing and accessories. By 1969, Cal had added the Birdcage Theater to his ghost town emporium. As a teenager, he had won a prize for singing in falsetto voice. This, with his circus and vaudeville experience, prepared him to record original skits, songs, and dialogue, and activate the “actors” by placing speakers in the back of their heads connected to battery-powered tape recorders. “The Fantasy Doll Show” included dance, dolls riding bicycles, and performing acts of daring do, and the admission was fifty cents. Each doll had a tip can. If a visitor was especially delighted with a particular feat, he or she could make a contribution toward the purchase of perfume or a piece of jewelry for the performer.

In March 1972, Cal had a heart attack. As Ruby related to filmmaker Allie Light in 1974, Cal had been trying to fix the windmill and he fell down in the yard. “He told her he was dying. She had no help, no telephone, and no one passed on the road. So he died. He lay in the yard all afternoon because she couldn’t move him,” said Light. Calvin had asked Ruby to burn the dolls when he died, but she did not, preferring to keep the site intact as long as she was able. When Ruby died in 1980, the dolls were dispersed, and Possum Trot was no more.

Stacy C. Hollander, “Calvin Black and Ruby Black,” exhibition brochure for American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2020).