Raphaël Lonné, like Madge Gill and Augustin Lesage, claimed that he used doubles or “ghosts” in order to go further and further into the deep layers of his being. In February 1950, Lonné—a postman from a small town in the Landes region of France—found himself in front of the disordered scribbles he had created during a spiritualist session: “Suddenly, I started. I was forced to follow the movement of my hand. On the sheet, there were formless things, and at the end, a portrait made of arabesques and spirals representing a human figure, half-man half-animal, a creature who wanted to be born. Thereby, I was nominated a ‘mediumistic painter.’ I lay my hand down and I let myself go. It’s like a dream that comes true gradually. I stay calm and quiet.”

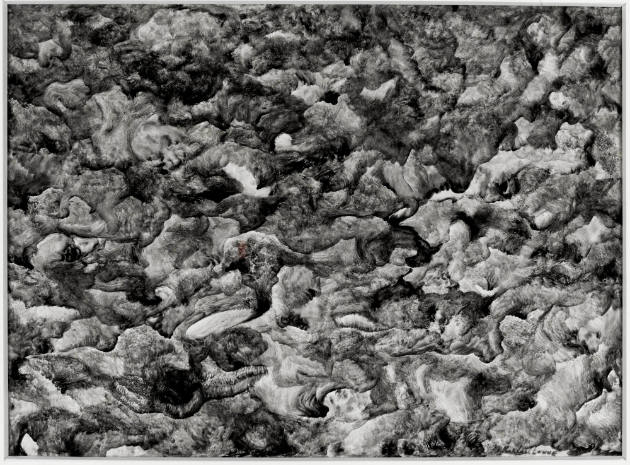

Lonné’s drawings can be described as a form of graphic writing. They offer a multiplicity of meanings, as forms and subjects seem to gradually shift, intermingling in a compact and underground design. The repetition of units suggests a constant extension beyond the limits of the paper. Here, they resemble signs and inscriptions in adorned capital letters, like drop caps, shaping a city’s name or a woman’s name; he would say that these images might be places or people who played a role in his previous life. In this way his compositions become imaginary landscapes, alluding to wildlife and mineral forms.

Altogether, Lonné created about one hundred works, most of which date from February 1950 to the first months of 1951. In the beginning, he traced the tumultuous, assured, and delicate lines with graphite pencil, then intermittently with ballpoint pen. For a few years, Lonné denied being responsible for these drawings, explaining he had no artistic skill. This performative mechanism would start right away once a pencil was in his hands: he would then channel whatever the dead wanted to give him, until the work was finished. His works developed mechanically by adding horizontal layers from left to right and top to bottom. Later, faced with the growth of his artistic recognition, Lonné eventually abjured his beliefs. Presenting himself as the servant of “artists from the invisible world” had been a useful excuse to justify the continuation of his practice.

Adapted from Valérie Rousseau, “Raphaël Lonné” in Valérie Rousseau (ed.), When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2015).