Record Details

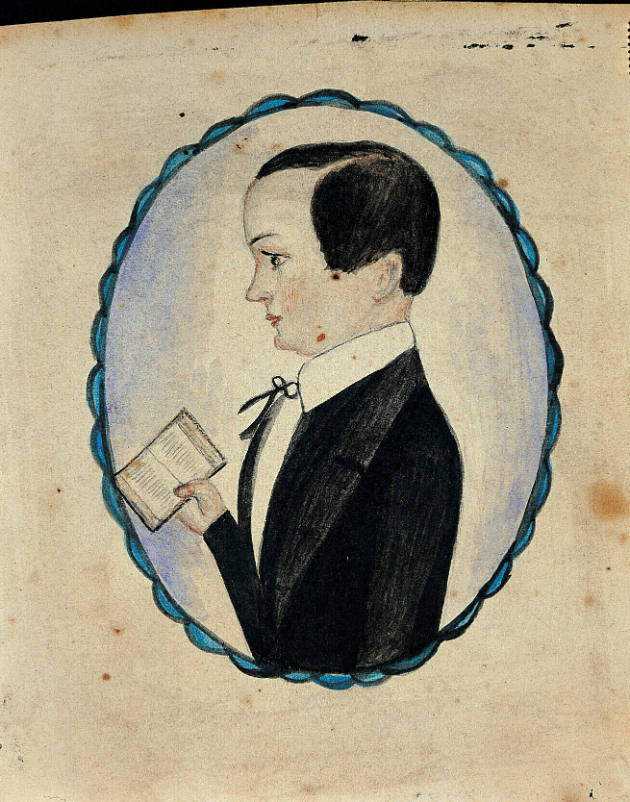

Young Boy Holding an Open Book

Painted portraiture was so common in American households before the middle of the nineteenth century that in 1829 critic John Neal was moved to comment, “You can hardly open the door of a best room anywhere, without surprizing or being surprized by the picture of somebody plastered to the wall, and staring at you with both eyes and a bunch of flowers.” Americans would have continued to have their portraits taken in oil or watercolor but for the introduction of a technique that ultimately was to render the painted portrait obsolete—daguerreotypy. This photographic process, which made its way into the farthest reaches of the American public soon after its introduction in 1839, was fast and inexpensive, could be used to produced multiples, and achieved a perfect likeness with which painted portraiture could not compete, though paintings did offer options of scale and color not available through the new process. For some time, while daguerreotypy was a new art, the two techniques overlapped, and the same artisans often practiced both methods of portraiture.

This small watercolor derives its format from the daguerreotype, the scalloped oval border imitating the stamped brass mats that conventionally surrounded the mechanical image. It is one of at least fifteen watercolor miniatures by Thomas Skynner, an artist about whom virtually nothing is known. According to signed and dated watercolor and oil portraits, Skynner painted in New Hampshire, upstate New York, and even Virginia. His oils are generally pairs of portraits with the couples inclined toward each other from facing canvases. The peculiar treatment of hands—which have been described as “boneless”—the awkward foreshortening, eyelashes painted as a series of small dots, and shared treatments of costume have been cited as traits of the artist’s work in oil.

Stacy C. Hollander, "Young Boy Holding an Open Book," in American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2001), 332.