Record Details

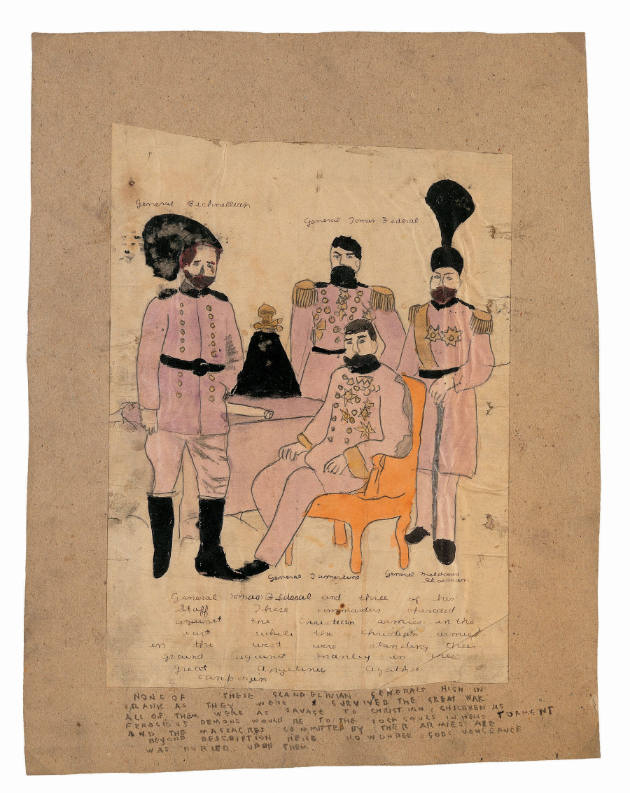

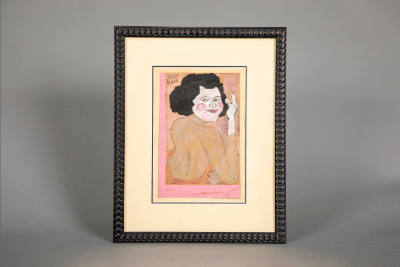

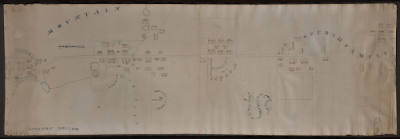

General Bichnellian, General Tomas Federal, General Tamerline, General Meldonia Shoeman

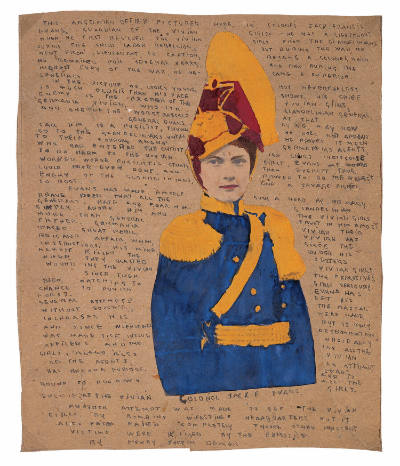

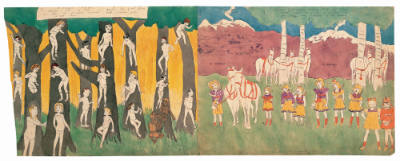

Bereft and abandoned throughout his life, Henry Darger was a solitary figure. He worked at menial jobs in Catholic hospitals, attended mass several times each day at a Catholic church near his home, and lived quietly in a one-room apartment in Chicago. He gave no hint that behind his closed door, amidst the debris and detritus he collected, the twine balls, and empty Pepto Bismal bottles, was a magnificent and complex world filled with magic, beauty, and color—but also great cruelty, violence, and heroism. Beginning in 1910, Darger began to write his epic The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is known as The Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco Angelinnean War Storm, caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. When he was through, the typewritten manuscript was 15,145 pages long, and was contained in fifteen volumes. Darger’s ambitious vision was essentially literary in conception but it was expanded through around three hundred luminous watercolors miraculously painted using inexpensive children’s watercolors on cheap newsprint ranging in size from single sheets to panoramic scenes on pieced paper many feet in length, all bound into three huge volumes. The tale encompasses timeless themes of good versus evil, acts of astounding bravery and craven cowardice, kindness and horror, all centering on the child slave rebellion, led by the seven brave Vivian sisters, against the unimaginable acts perpetrated by the enslaving anti-Christian Glandelineans. The detailed descriptions of military engagements were heavily influenced by Darger’s knowledge of the American Civil War, and he chronicled the flags, maps, and officers in separate journals. In addition to his epic, Darger kept various journals, wrote a little-known second novel that revisits the Vivian Girls, and, in 1963, ten years before his death, embarked upon an autobiography that filled eight volumes, The History of My Life.

Darger was born in Chicago. Shortly before his fourth birthday, the little boy lost his mother, who died after giving birth, and the baby sister who was presumably given up for adoption. A few years later, his father placed him in a Catholic institution for young boys. Despite his apparent intelligence, his behavior caused his removal to the Lincoln Asylum for FeebleMinded Children in Lincoln, Illinois, an institution that housed 1,500 children. Darger made several attempts to escape, finally succeeding in 1909, when he trekked almost two hundred miles back to Chicago by foot. In 1930, Darger rented a single, large room from artist and industrial designer Nathan Lerner that he inhabited until he became too feeble to climb the stairs. He went to live in the Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Elderly, ironically, the home in which his father had died years before. Within six months of being removed to the facility, and one day after his eighty-first birthday, Henry Darger died. It was not until Lerner was cleaning out the apartment that the astounding breadth of Darger’s private world of the imagination was discovered.

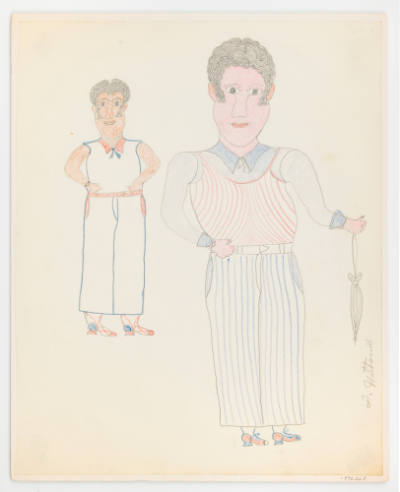

From the very beginning, Darger relied on the use of published images to draw the figures that populated his paintings culled from newspapers, magazines, comics, and coloring books. Initially, he painted directly over published images, cutting them out and using them as collage or tracing the figures same-size. Around 1944, he began to have negatives from the small pictures made at his local drugstore that were then enlarged to 11 x 14 inch. In this manner, he created a library of 246 images that were stored in their original brown envelopes and labeled as to their intended uses. Most of the large paintings show carbon residue left from tracing the figures onto the newsprint that Darger typically used. He altered the figures by adjusting their sizes, moving the positions of the limbs, and either removing the clothing or changing details of the dress.

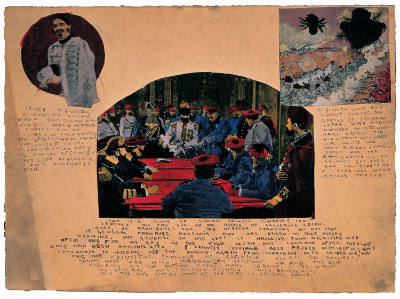

These two works evidence Darger’s fascination with military history and trappings. He has portrayed four of the generals responsible for some of the most heinous acts against Christian children described in his saga, including the murder of Annie Aronburg, whose martyrdom early in the rebellion inspired the leadership of the Vivian sisters. The persona of Aronburg was based upon a cherished photograph clipped from the Chicago Daily News in 1911, at the early stages of Darger’s opus. It depicted five-year-old Elsie Paroubek, an angelic-looking child whose murder in the Chicago area was closely followed by millions of readers. Darger later misplaced the precious photograph, launching him into a period of sorrow and rage that manifested in horrific violence perpetrated in the pages of his story. As time passed, and his prayers to God for the return of the photograph went unanswered, the successful outcome of the rebellion was threatened, As he wrote in his journal: "October, 1912: Prediction and Threat: Despite the new situation in the war, petition must be granted before March 21, or change will come in favor of the enemy. H.J.D." These renderings display the hateful flag of the Glandelinean nation and a formal portrait in the war room of the most savage high-ranking generals of the Glandelinean army, responsible for the murder of Annie Aronburg.

The alternative universe that Darger created is both strange and familiar. Its violence finds real-life parallels in the depredations of world war and other conflicts; its beauty and quest for moral victory is heartbreaking. The paintings cut to the heart of fear that underlies the veneer of family life: the fear of loss in a volatile world.

Stacy C. Hollander, "Untitled (Portraits of General Bichnellian, General Tomas Federal, General Tamerline, and General Meldonia Shoeman), mid-20th century, Untitled (Flag of Glandelinia), mid-20th century" exhibition copy for American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection. Stacy C. Hollander, curator. New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2020.

Object information is a work in progress and may be updated with new research. Records are reviewed and revised, and the American Folk Art Museum welcomes additional information.

To help improve this record, please email photoservices@folkartmuseum.org