Record Details

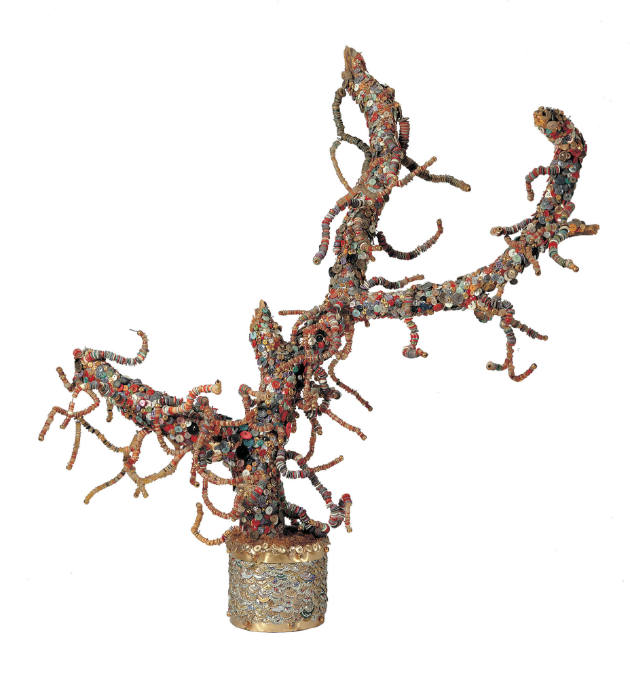

Button Tree

Artist

Gregory "Mr. Imagination" Warmack

((1948–2012))

Date1990–1992

Place/RegionChicago, Illinois, United States

MediumWood, cement, buttons, bottle caps, and nails

Dimensions56 x 34 x 60 " (142.2 x 86.4 x 152.4 cm)

Credit LineGift of the artist

Accession number2000.13.1

CopyrightCopyright for this work is under review.

DescriptionObject information is a work in progress and may be updated with new research. Records are reviewed and revised, and the American Folk Art Museum welcomes additional information.

To help improve this record, please email photoservices@folkartmuseum.org