Record Details

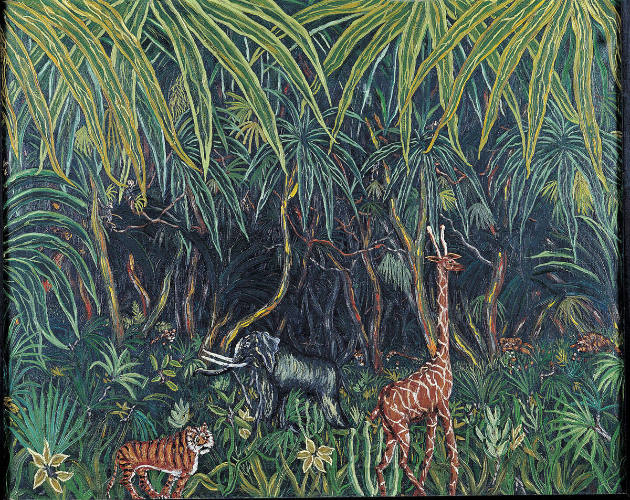

Jungle Scene

Artist

Victor Joseph Gatto

((1893–1965))

Date1942

Place/RegionProbably New York

MediumOil on canvas

Dimensions24 × 29 1/2"

Credit LineGift of Ellin and Baron Gordon in memory of Herbert Waide Hemphill, Jr.

Accession number2000.9.1

CopyrightCopyright for this work is under review.

DescriptionObject information is a work in progress and may be updated with new research. Records are reviewed and revised, and the American Folk Art Museum welcomes additional information.

To help improve this record, please email photoservices@folkartmuseum.org