Record Details

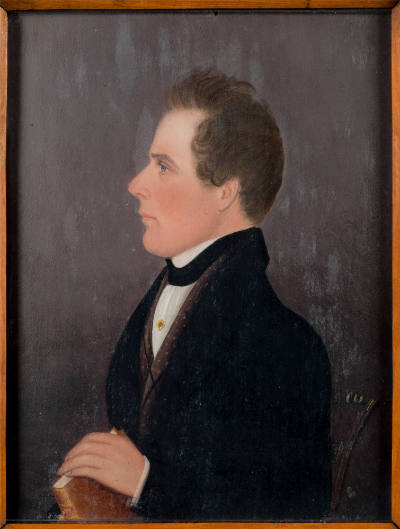

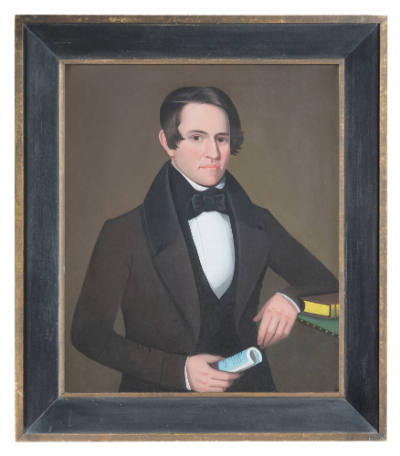

Young Physician Holding a Surgical Saw

Frame Dimension: 11 1/8 x 9 1/8 x 1 1/4 "

A tradition of painted profiles, inspired by heroic portrait medallions and coins from ancient Roman culture, was well established in the United States by the 1760s and 1770s. This interest was deeply reinforced by the publication of Johann Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy, Designed to Promote the Knowledge and Love of Mankind and the ensuing demand for accurate likenesses that gave insight into a sitter’s character. By the first years of the nineteenth century, the introduction of mechanical devices such as the physiognotrace, which captured the exact outline of a profile revolutionized the general availability of profile portraits at a modest expense. Among the best-known practitioners was French artist Charles Balthazar Julian Fevret de Saint-Memin (1770–1852), who worked in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. After 1802, the physiognotrace was also used in Philadelphia’s Peale Museum, artist and founder Charles Wilson Peale having gained the patent rights to the machine. As demonstrated by the proliferation of mechanically assisted profiles, however, the device was used with slight variations by many practitioners throughout the eastern United States.

Several portraits by this as-yet-unidentified artist are known, all painted in a precise manner on small wood panels. The young physician portrayed in this example holds a Tenon-type amputation saw. Although some Americans could afford to study surgery abroad, the vast majority of local physicians also practiced surgery without the benefit of foreign study in major medical centers. In the period before anesthesia, surgery was an ordeal whose most important element was speed. In 1792, a young man in Mansfield, Connecticut, wrote, “Yesterday I attended upon the amputation of a thigh which opperation was performed by the famous Doct. Tudor and I will say sir between you and I had you been present I believe your bowels would have yearn’d through anxiety & pitty for the opperation was protracted to the unreasonable length of forty minutes or more.” To relieve the pain and anxiety of waking surgery, practitioners tried mesmerism and other experimental techniques, but it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that inhalation anesthesia was devised.

Stacy C. Hollander, "Young Physician Holding a Surgical Saw," in American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2001), 333.