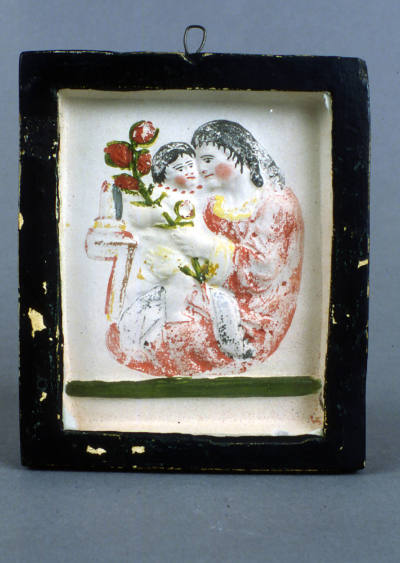

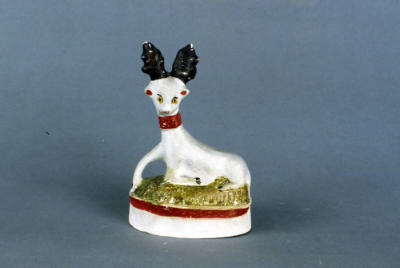

Record Details

Chalkware: Seated Cat

Three-dimensional images cast of calcined gypsum, known today as chalkware, were produced in America as early as 1768, when stonecutter Henry Christian Geyer advertised plaster of Paris busts of famous public figures as well as “Animals such as Parrots, Cats, Dogs, Lions, Sheep, with a number of others too many to enumerate.” By the middle of the nineteenth century, chalkware provided an inexpensive alternative to imported ornaments fashioned from porcelain, earthenware, and other materials for the rural consumers hungry for decorative objects for their homes. It was long believed that chalkware was made by Pennsylvania Germans because so many examples survived in eastern Pennsylvania, a region with a heavy Germanic population. However, it has since been established that nineteenth-century chalkware was made primarily by Italian immigrants living in urban areas, such as Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Chalkware was distributed widely by itinerant “image peddlers,” a fact that is reflected in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868): Amy March, living in Concord about 1862, speaks of her “most precious plaster rabbit.”

Chalkware was made by pouring a creamy mixture of plaster of Paris into a two- (or more) part negative mold, which was held together for casting. The mixture was swirled around to coat the interior of the mold, and the excess was removed. After the plaster of Paris air-dried, the mold was removed, revealing the resulting hollow, three-dimensional form. The final step was to sand the seams where the molded parts were joined and to paint the chalkware in tempera, watercolor, or oil-based paint. Few molds survive today because they themselves were made of the fragile plaster of Paris and frequently broke or lost the clarity of the impression and were discarded.

Stacy C. Hollander, "Seated Cat," in American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2001), 346-47.